Japanese videogame magazines can be difficult to read. Especially if, for example, you're not able to read Japanese. But I am (after a fashion), and even I get a headache from navigating the maze of Weekly Famitsu. A good headache, though -- the kind which, when it clears, leaves you with an epiphany. Here's why.

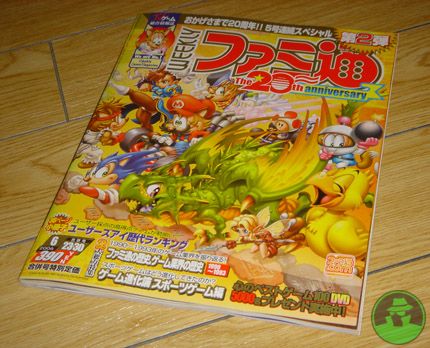

Famitsu's cover art has always been provided by Susumu Matsushita, one of the most distinctive and widely published cartoonists in Japan. His unique way of drawing characters -- lovely bulbous eyes and clay-like texture -- can be seen everywhere, from Famitsu to various Capcom Super Famicom classics to comestibles and conbini branding. And the best thing about his Famitsu work is that the composition of its cover artwork is so hectic. You can keep every issue as an artistic videogame memento. As far as I'm concerned, no other game mag in the world can match Famitsu for its looks.

Between the covers are 210 pages of almost-as-dazzling gaming joy. There are large sections devoted to readers' own artwork, too, and most of the contributions are indicative of Japanese game fans' innate artistic skill. Of course, while we're talking aesthetics, I should also point out that Japanese characters are way cooler than the Roman alphabet. Naturally, Japanese magazines look more interesting than American or European game mags can ever hope to. But are Japanese mags actually interesting to read, you say?

In a word: sometimes. In three: but not always. It depends, of course, on what you want to read, but Famitsu and its cousins (single-format mags such as Famitsu Xbox 360 and single-company publications such as the excellent Nintendo Dream) tend to cater primarily to gamers who wish to read lengthy previews and even lengthier game guides. The middle bit -- you know, the actual criticism of games -- is served on a teaspoon, a tiny dose of one paragraph per reviewer.

Famitsu's review scores, attained by tallying four writers' out-of-ten grades, are pored over in the West as though they're some kind of code for access to a safe of prescience. And often, I must admit, those review scores are reasonably accurate. But really, that's all they are: numbers; numbers backed up with only the briefest of "this is good and so is this, but this bit's not very good" reviews. Hardly critical analysis at all, really.

However, where Japanese writers put in real effort -- and where they are arguably more talented than we Western hacks -- are the 'before' and 'after' stages: previews and guides. Often previews go on for a dozen pages or so, leaving no stone unturned. By the time the game in question is released, for better or for worse, you can have a comprehensive idea of what to expect and when to expect it. It's all because of the privileged relationship Japan's videogame press gang has with Japan's world-famous software companies.

Japanese interviews with Japanese developers, unsurprisingly, are lucid and revealing. Thanks to well-kept relationships and less reliance on PR people, Famitsu and company have direct access to some of the most important minds of the videogame world. And as a byproduct of this loved-up working relationship, plus a geographical advantage, Japanese magazines break Japanese videogame news earlier than anyone else can.

So is Famitsu worth 390 yen? For the cover alone, I say yes. And inside, while I avert my eyes from hardcore previewography and pay only passing attention to those piddling little "reviews," I can usually find something that is interesting to read.